As if toggling between HBO and the History Channel, Millet’s extravagant narrative is regularly interrupted by deadpan segments on the hideous, biblically proportioned power of thermonuclear weapons.

–Village Voice

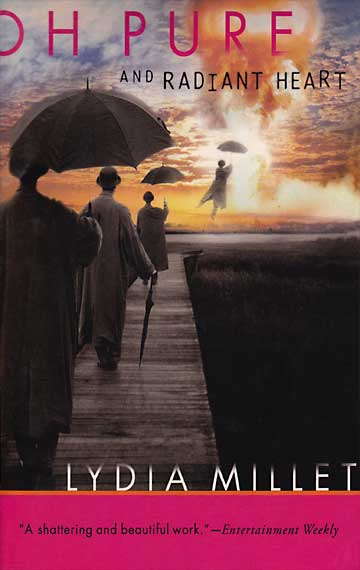

From the publisher

Oh Pure and Radiant Heart imagines a world in which the three geniuses who were key to the invention of the atom bomb — physicists J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard — are displaced to contemporary America at the moment history’s first mushroom cloud rises over the New Mexico desert in July 1945. When the scientists appear in Santa Fe in 2003, Ann, a reference librarian, and her doting husband Ben take them in, and with the long-dead physicists for houseguests are swept up in a quixotic and calamitous quest.

Excerpt

I. THE MEANING OF THE PORKPIE HAT

1

In the middle of the twentieth century three men were charged with the task of removing the tension between minute and vast things. It was their job to rend asunder the smallest unit of being known to be separable from itself; out of a particle so modest there are billions in a single tear, in a moment so brief it could not be perceived, they would make the finite infinite.

Two of the scientists were self-selected to split the atom. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi had chosen long before to work on the matter, to follow in the footsteps of Marie Curie and her husband, who had discovered radioactivity.

The third man was a theoretical physicist who had considered the subject of the divisible atom among many others. He was a generalist, not a specialist. He did not select himself per se, but was chosen for the job by a soldier.

Thousands worked at the whims of these men. From Szilard they took the first idea, from Fermi the fuel, from Oppenheimer both the orders and the inspiration. They built the first atomic bomb with primitive tools, performing their calculations on the same slide rules school children were given. For complex sums they punched keys on adding machines. Their equipment was clumsy and dull, or so it would seem by the standards of their children. Only their minds were sharp. In three years they achieved a technological miracle.

Essentially they learned how to split the atom by chiseling secret runes onto rocks.

And it should be admitted, the concession must be gracefully made: in the moment when a speck of dust acquires the power to engulf the world in fire, suddenly, then, all bets are off. Suddenly then there is no idea that cannot be entertained.

On a clear, cool spring night more than half a century after the invention of the atom bomb, a woman lying in her bed in the rich and leisured citadel of Santa Fe, New Mexico, had a dream. This itself was not surprising.

To be precise it was less a dream than an idea in the struggle of waking up. She thought the dream as she began to rouse herself and she was left, after waking, with an urgency that had no answer. She was left salty and dry, trussed up in a sheet, the length of her a shudder of vague regret.

In the dream a man was kneeling in the desert.

The man was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Father of the Atom Bomb. The desert was an American desert: it was the New Mexico desert, and the site was named Trinity. Oppenheimer named it that. He gave lofty names to all his works, all except Fat Man and Little Boy.

These details would be revealed to her later. At the time nothing had a name but the man.

The man’s porkpie hat was tipped forward on his head and his pants were torn. His knobby knees were scratched and the abrasions were full of sand. She almost thought she could feel the sand against her own raw flesh, where the grains agitated. It may have been dust on the sheet beneath her, or, further removed, dust between the sheet and the mattress, a pea dreamed by a princess.

He was bent over abjectly, his face turned to the ground.

Then there was the flash, as bright as a thousand suns, which turned night into day. And on the horizon the fireball rose, spreading silently. In the spreading she felt peace, peace and what came before, as though the country beneath her, with its wide prairies, had been returned to the wild. She saw the cloud churning and growing, majestic and broad, and thought: No, not a mushroom, but a tree. A great and ancient tree, growing and sheltering us all.

The sight of it was poetry, the kind that turns men’s bones to dust before their hearts.

At this point in the scene she confused it with the Bible. The man named Oppenheimer saw what he had made, and it was beautiful. But when he looked at it, the light burned out his eyes and turned him blind.

She saw the rolling balls of the eyes when he righted himself to face the tree, and they were white like eggs.

Back then she knew nothing about Oppenheimer’s life: not who he was, not the identities of places, not the fact that the sand in the scrapes in his knees would have been the sand of the valley with the Spanish name Jornada del Muerto, Voyage of the Dead. There were infinite details she could not recognize, infinite details beyond her awareness in her own half-idea, in the deep blind territory of what is not known to be known but is known all the same.

Also there was what she knew without knowing why she knew it, for example the phrase brighter than a thousand suns. She recalled these words without a hint of where they came from or how they had first been imprinted on her memory. She did not know what “brighter than a thousand suns” would mean, how a brightness so bright could be outdone. The eye is not equal to even one sun, she thought. Straight, unwavering, bold, the eye cannot abide it.

A thousand suns? The eye could never adapt.

Or maybe once it is blinded the eye is transformed, she thought, and ceases to be an eye at all.

How much is learned unconsciously? It must be vast, she thought. We sweep through fields of knowledge and later all we can see is the dust that clings to the hems of our clothes.

Of course the scene itself, the dramatic idea that was not quite as unconscious as a dream, might have simply been a blurry cognitive rerun of any number of World War Two documentaries. It might have been a fragment from television, a black-and-white epic of scarred and pocked newsreels interspersed with propaganda footage from the Nuremberg rallies. She might remember young boys marching in synchronicity and jutting out their arms in salute; further she might recall the chilling but majestic banners hanging long and thin and several stories high above the seemingly endless crowds, their spidery symbols rippling like water in the wind.

And over this she might recall the droning, authoritative voice of a British narrator.

Afterward she remembered the name. She could not forget the name, in fact, in the way a bad jingle overstays its welcome, tinny and insistent, lodged in the neural pathways of the brain. It was a famous name, or a name that had once been famous anyway, before she was born when her parents were young, when the Japs got what was coming to them, and later still when the drunkard McCarthy was hunting down Communists.

It was Oppenheimer, J. R.

Also the words The Father of the Atom Bomb.

A few days before, in waking life, she had seen the name at a small garage sale in a driveway, on the yellowing pages of a dogeared copy of an old magazine from 1948, titled Physics Today. At the garage sale she had purchased a trivet, and the trivet had been sitting on this magazine when it caught her attention. She did not need a trivet, and in particular she did not need a porcelain trivet decorated with watercolor-style renderings of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. But she felt a need to compensate the woman who was trying to sell it. The woman had a gentle gaze and a distracted manner and admittedly also a flipper for one arm.

Later, when she thought of the magazine cover, she also thought of printed words on the trivet: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

On the cover of the magazine was a picture: the porkpie hat perched on some pipes, possibly in a factory. Later she learned the porkpie hat had been a stand-in for Oppenheimer at the height of his fame. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when the bombs had been dropped, the war was over and the Father of the Atom Bomb was a hero, the hat actually posed alone for photographs.

As an ambassador, the hat had a simple message. It said: I am worn by a gentleman.

It said: We are all gentlemen here. •